Apartment Vacancies Are Peaking In Expensive Markets

Introduction

After years of steady price increases, 2020 brought the nation’s rental market to a halt. Typically rents rise during the busy summer season, but this year apartments across the country are on average renting for about two percent less than they were pre-pandemic.

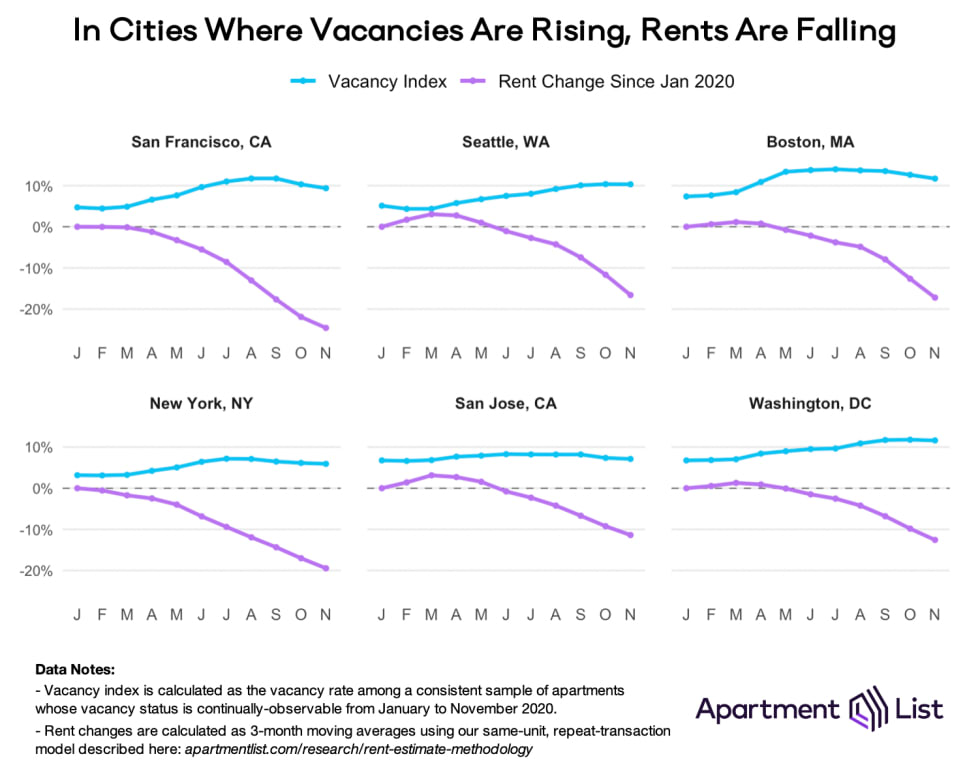

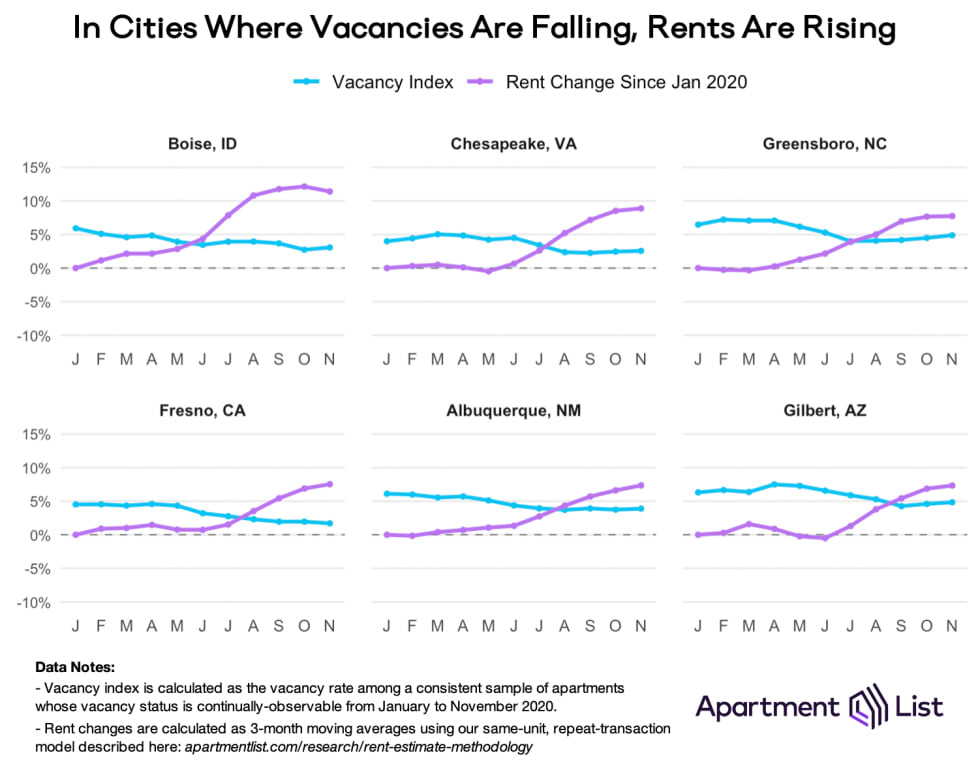

But as we uncovered in our latest National Rent Report, this does not mean that cities are getting universally cheaper. This year, in particular, brings tremendous regional variation. The national rent decline is composed of a handful of expensive cities where rents are falling rapidly (e.g., San Francisco, New York, Seattle), offset by many smaller, more-affordable cities that have actually gotten pricier over the course of the pandemic (e.g., Boise, Fresno, Tucson). In this report we analyze vacancy rates to offer clues about why prices are dropping in some markets and rising in others.

For this we developed a vacancy rate index, which relies on a large sample of apartments in each city whose vacancy status is continuously-observable throughout 2020.1 This “same-property” approach ensures that our vacancy index is not affected by compositional changes in the market, such as new apartment buildings coming online. In this way it is similar to our “same-unit” rent index, which also controls for compositional effects. When we plot these vacancy and rent indices together, we see an inverse relationship: prices fall as vacancies rise, and vice versa, as rental markets across the country struggle to react to the sudden shock of the pandemic.

Vacancies, Rents, Supply, and Demand

The pandemic has altered the types of housing that many renters desire and can afford. As much of the country’s entertainment and work moved online, the premium of being “close to the action” in cities and job centers began to fade, and previously overlooked suburbs and small metros began to heat up. This demand shift was a shock to the rental market, which can manifest in price and vacancy changes as the market finds a new equilibrium.

We see this playing out clearly in 2020. Take for example the six cities with the steepest rent declines this year; from March through June, all six saw vacancies rise as prices started to fall.2 In Seattle, San Francisco, and New York, today’s vacancies are double what they were before the start of the pandemic, and in Boston and Washington, D.C., more than 10 percent of units in our index are empty. With so many vacant apartments to choose from, prospective renters have leverage while landlords must drop their prices to attract new tenants.

The opposite is true in cities that are getting more expensive. Despite the economic fallout of the pandemic, a number of affordable midsize cities have attracted a steady stream of new renters. This has led to low vacancy rates and a competitive market whereby landlords can raise prices confidently knowing renters have fewer options to choose from. In many ways, these smaller markets are now more competitive than the expensive cities listed above. As a result, rent prices are up more than 10 percent in Boise, more than 8 percent in Chesapeake, and more than 7 percent in Greensboro, Fresno, Albuquerque, and Gilbert.

Our team has compiled these data for nearly 100 large and medium-sized rental markets throughout the country. Use the interactive chart below to compare the vacancy and rent indices in your city, or download the raw data.

Why Is This Happening?

A driving force behind these vacancy shifts is migration - where renters are coming and going. In expensive cities, vacancies are on the rise because 1) some renters are leaving and 2) others are choosing not to come. While a full-blown “urban exodus” seems unlikely, the pandemic has certainly shifted many renters’ housing preferences. Some are becoming homeowners, while others relocate to more affordable cities as the pandemic shuts down urban amenities and encourages living space.

But beyond that, in 2020 many cities did not receive their annual summer influx of new residents and newly formed households. In particular, many college students and recent graduates who might move to big cities are instead living at home longer thanks to online coursework, slower hiring, and greater remote work opportunities. Meanwhile, a wave of young adults moved back in with family, at least temporarily.

In the nation’s more affordable regions, demand for apartments grew steadily throughout the year. These cities became destinations for renters moving out of necessity as well as opportunity. Some have no choice but to downsize their housing costs given the state of the economy. Others who are in good financial standing may do the same if they are no longer tied to an expensive city by their job. In other words, affordable markets have become magnets for renters spanning the entire economic spectrum, and this increased demand is filling vacancies and driving up prices.

Conclusion: Have We Hit the Bottom?

As we leave 2020, some markets appear to be turning a corner, with vacancy rates gradually reversing course. But today we still find ourselves in the slowest season for renting, and with a low volume of people moving during the winter, it is unlikely that the trends that have emerged over the course of 2020 will be undone quickly. The coming spring and summer will be critical; widespread COVID vaccinations could revitalize urban areas and relieve some pressure from smaller rental markets. But until then, expect price convergence to continue - pricey cities will get cheaper while once-affordable cities continue getting more expensive.

- Since our vacancy index is calculated from units listed on the Apartment List marketplace, it may skew towards newer multifamily units that make up the majority of inventory on site. A comprehensive city-wide vacancy rate may differ after considering the older units and single-family rentals that are underrepresented on our site.↩

- This rise in vacancies is not a typical seasonal trend. In previous years, the vacancy index in these cities was mostly stable throughout the spring and summer.↩

Share this Article